Conclusion

This is the end of the first part of our critical tract about the militant proletarian movement in the Czech Lands, which contributed in its own way to finishing the World War One and gave rise to the revolutionary perspective and tendencies. Preceding pages contain a lot of factual information, some of which are essential for understanding to the given class movement and others only place it into the context and emphasize interesting details and episodes that should not fall into oblivion. All of them are intertwined by attempts at articulation of programmatical lessons, which we have arrived at through the analysis of the then movement. We are aware that precisely these conclusions may finally get lost for the reader. Which is the reason, why we consider it as necessary to make a balance sheet of all strengths and weaknesses of the 1914-1918 struggling proletariat in a purely programmatical text trying to underline all lessons elucidated for us by the then working class’ brave struggles as well as tragic defeats.

It is an undeniable fact that the movement analysed by us was born from contradictions distinctive in the capitalist society and leading to the outbreak of the world war too. Irrespectively of bigger or smaller resistance of some proletarians, at the beginning the great majority of our class obediently marched to be slaughtered. Thus it negated itself as a class in the same way as it does in times of peace, when social peace rules – the war is just a continuation of this situation, in which bourgeoisie is winning in class struggle up to the point, where proletariat loses its conscious being and Capital dominates and exploits it wothout bigger problems. During wars inhumanity of our existence, however, reaches its highest degree as Capital is solving productive forces’ surplus through destruction and strives to maximize exploitation. Increasing work norms, militarisation of labour, decrease in real wages, a mass engagement of women and youngsters in the industrial production, decreasing amount of food available on market, falling rations and… hunger became faithful fellow-travellers of the bloodbath on battle fronts.

It was precisely the war massacre and the brutal increase in the rate of exploitation what led an important minority of the working class towards a revolt against horrible conditions of life. This minority did not want to passively put their lives on the altar of Capital’s prosperity and reproduction anymore and set on struggling for satisfaction of their human needs. Its struggle for bare physical survival, epitomised by an “economic” or “reformist” demand of “bread” and “peace”, was in practice directly attacking “its own” state’s politics and contributed to the state’s defeat. Which means that its struggle was implicitly (and many times even explicitly) “political” – revolutionary defeatist.

The vanguard proletarian minority was rebelling spontaneously – it did not need any leftist missionaries, bringing “class consciousness” to the masses drop by drop and leading them through knotty paths of radically appearing reformism up to the revolution (it is not important whether in the form of trotskyist campaigns for transitional programmes or anarcho-syndicalist unionism which is supposed to be a “school of revolution”). As the Left (or Social Democracy in all its forms) was standing then on the side of Capitalism, as it is standing there now, the proletarian movement came into existence outside of the framework, initiative and effective control of traditional left-wing organisations: bourgeois-socialist political parties/federations and unions. From the viewpoint of proletariat’s historical movement, the war, growing international class movement and the global communist perspective’s birth tore down leftists’ revolutionary mask and exposed their pro-capitalist face. Formerly sworn enemies – “marxists”, national socialists and “anarchists” – were combining their forces in a prefiguration of the People’s Front, in order to effectively nurish all weaknesses of the working class’ movement and to get a reform and maintanance of bourgeois state on order of the day instead of the social revolution. Which for example means that almost two decades before Spanish “anarchists” from the CNT-FAI joined the Republican government and thus prefered an anti-fascist alliance with bourgeoisie to the revolution, Czech “anarchists” threw away their revolutionary tendencies and anti-statism in favour of the national-liberationist counter-revolutionary project and enthusiastically integrated themselves into the capitalist state’s structures.

Unlike inheritors of leftist ideological families, we do not fetishize any forms of organisation. No organisational form has ever been and will ever be a guarantee of the revolutionary content, a guarantee of the revolutionary victory, an eternally valid answer to the question of how proletariat should organise itself as the revolutionary class. Social Democrats’ formal political organisations and unions (parliamentary “marxist” or national socialist parties, legal or illegal disciplinned parties of professional “revolutionaries”, synthetic or platformist “anarchist” federations, trade unions with a correct political leadership, “anarchist” or “apolitical” syndicates) have been expressions of workers movement’s weaknesses and a counter-revolutionary tendency since their beginning. Other forms of our class’ association were materialisations of working class’ self-organisation in particular moments of its movement: soviets or workers councils, factory committees, free collectives and communes, “red” armies, guerilla units, autonomous zones… The 1917-1918 movement in the Czech Lands gives evidence that not even self-organisation is necessarily a guarantee of complete unfolding of the revolutionary content.

Let’s have a look at particular examples. As far as our limited knowledge allows us to say something, we can state that the then associations of struggling proletarians had essentialy several forms stemming from specific conditions and experiences of their participants. For instance, deserters’ gangs, so called Green Cadres, at first refused to fight in the imperialist war and subsequently – in order to survive – had to fight against repressive forces of the state (murdering gendarmes and shoot-outs with them) a expropriate bourgeoisie (eg. robbing rich peasants). The social meaning of their practical activity was thus directed against “untouchable” capitalist relations: against the state power and private property. Green Cadres in the Czech Lands organised themselves on the basis of bare physical survival of their members and of a certain level of class consciousness connected to it. It was even giving birth to the perspective of social revolution class. Nevertheless, Green Cadres did not achieve fully developed class self-consciousness and the revolutionary programme.

Inside militant soldiers’ hard cores, which stood behind preparation of military mutinies, the situation was not much brighter (or better said redder) and clear. Each of above described mutinies was, in the social content of their particular practice, an act of the proletarian struggle against the war, despite some of its participants were introducing into the struggle nationalist and other weaknesses. Nucleuses of military militants were able to incite those mutinies, but not to give them a clear communist direction. Unlike their comrades from Kragujevac and Kotor, Rumburk militants achieved, through previous experience and aktivity, a somewhat higher rate of class consciousness and were able to articulate revolutionary aspirations, which were, however, vague. That is why their actual steps were also tragically insufficient or openly mistaken. All militant nucleuses shared the same weakness: they primarily saw themselves as soldiers’ business and not as an integral part of the working class and its organisational expression. Irrespectively of the fact, whether mutineers spoke about revolution or not, in practice all of them were capable of attacking the imperialist war logic and the bourgeois army’s hierarchy and thus the state’s hierarchy. But they were unable to overcome the military aspect of their struggle, relate to other sections of the proletariat and attack all the web of capitalist social relations.

Even industrial workers’ delegates committees were contradictory. Those committees were nothing new. They were the traditional lowest organisational unit of left-wing groupings and trade unions. However, passive collaboration of unions and all the other formal parties or federations of historical Social Democracy with bourgeoisie significantly altered their nature. During the war, older skilled workers – antebellum members of those organisations – were forced to find a way how to organise and lead their struggle themselves, without unions and political parties, which, up till that time, had been selling an illusion that it is them who fights for proletariat’s interests. Thus workers appropriated delegates committees through which they had always immediately organised themselves. They turned the committees, that previously served to disorganise the struggle, into instruments for organising strikes. Their structures in factories and mines evidently dominated even to unskilled proletarians, who newly came into industry because of the starting shortage of labour forces. Even new delegates committees came into existence, based on momentary workers’ needs and designed only to fulfill one single task. By the end of the war in some of the militarised productions, even soldiers speaking foreign languages became delegates as they fraternised with local proletarians and sabotaged repressive functions that they were supposed to carry out. In practice, delegates committees represented an important part of class struggle and crystallization of class consciousness and revolutionary spirit corresponding to the level of the struggle. Nevertheless, they had never consciously cut the umbilical cord connecting them to their parent organisations. For instance in the Kladensko region, the delegates committees, which originally belonged to the CSSDWP, did not rely only on direct actions but they also tried to negotiate through counter-revolutionary mediators, i.e. party deputies, etc. Therefore, when the left-wing counter-revolution actively returns back on the stage with all its might, it again finds a lever for disorganisation of class struggle in workers’ delegates. Besides of the not completely questioned workers’ loyalty, it could also easily pick up the threads of all insufficient ruptures with Capital and its ideologies on the part of our class.

We have been able to search out only two organisational expressions of territorial centralisation of class struggle: the first workers council in Prague and the Revolutionary Workers Committee in Duchcov. Both these points of centralisation represented a higher level of the class movement as they meant a conscious endeavour to link individual groups and categories of struggling proletarians. It is especially true of the Duchcov Revolutionary Workers Committee as the Prague workers council was ephemeral – it was smashed by the Austro-Hungarian state’s repression and not demobilised by nationalism. Besides that, the extent of the movement’s centralisation, that it was expressing, was lower as the workers council was limiting itself only to Prague factory workers and anti-war and anti-monarchy actions. On the contrary, the Duchcov committee notified even in its name that its goal is more far-reaching: workers revolution. At the moment, we are not able to say more about it. We do not know, how exactly it functioned, if it involved only industrial workers or also other categories of proletarians. Nevertheless, we know that it was a magnet for all the regional proletariat, including women and youth – not employed in industrial production – and deserters. There were probably only very few such centralising forces, if any except of Duchcov. Even if they were an important step in the development of the movement, they were not immune to nationalist ideology, therefore they could be undermined by the national-liberationist counter-revolution even from within, through their own weaknesses – which might be happened even in the case of Duchcov.

Not even absence of organisation and spontaneous explosions of class violence are the guarantee of a successful proletarian revolutionary action. Furious crowds of rioting and looting proletarians (primarily women and children), who were attacking bourgeoisie’s private property and fighting repressive forces of the state in the streets, did not automaticaly come from riots to an armed insurrection. There were the same holes and weak points in their class consciousness as in the consciousness of all the others and they also became enthusiastic supporters of national liberation and it does not matter, whether of the Czecho-Slovakian, German or Hungarian one. Therefore, we can say that it is not even the movement’s militant practice, that a full unfolding of the social revolution follows from. And finally it is neither minoritarian “linkboys” armed with a formal written programme of the revolution, that is a redeeming recipe. Firstly, they can not voluntaristicaly reverse an unfavourable conjunction of objective and subjective conditions, a balance of forces unfavourable to the proletariat. Secondly, however revolutionary this programme could be, it can never grasp totality of the historical communist programme, which can be revealed only through the multiplying strength, activity and initiative of the class and many vanguard minorities that are born in this liberating historical motion towards the self-conscious revolutionary class.

Thus, Communists do not look for delusive guarantees of the revolutionary spirit and ideological recipes for a successful revolution, which eventually always turn to be just traps laid by social relations of the old world (of which we are both bearers and gravediggers) for proletariat’s subversive movement. We know that we have no other possibility than to interest ourselves in the social reality of our class’ movement and to derive the communist programme precisely from that. The programme is not a dead letter, once written by somebody – either Marx or Bakunin. It gets clarified and stems from practice of the class movement itself, even if it is as invariable in its foundations as the nature of capitalism, which the proletariat rises against. Communists reflect the highest points in proletarian class struggle as well as its defeats, its weaknesses and strengths, because only in this way we can stay on the field of proletariat’s historical interests and goals. Only in this way we can able to act and fulfill the tasks posed to revolutionaries by class struggle and revolution – if we can not do this completely in todays conditions of the spectacular triumph of counter-revolution, than surely in the future we will have to do this. And this activity – inseparably linked with practice – centralises itself in the communist organisation and realises through it, as by its nature this activity is an expression of contradictory social being under the Capital’s domination and proletariat’s self-awareness stemming from that and not a kind of individualist intelectual entertainment.

The development of proletarian associations and class consciousness as well as the birth of organised communist minorities is an inevitable consequence of contradictions present in our social position of workers. From these contradictions, from opposed interests of people absorbed by the capitalist mode of production arises a practical antagonism between two classes – proletariat and bourgeoisie – expressing itself through class struggle. Only on the basis and in the process of class struggle there can be a rapid development of class consciousness and a rise of our class’ revolutionary organisation. These are undeniably decisive elements for an outbreak of social revolution. In order to avoid a misunderstanding, once more we stress the fact, that they can not be brought to proletariat from outside – on the contrary, every attempt of this kind is from its beginning a counter-revolutionary effort of Social Democracy to pacify the insurgent class (eg. the leninist model of the party). The truly revolutionary organisation of the class – the Communist party – always grows organicaly and from below from the actual proletarian struggle and consciousness, from the proletarian autonomy. This programmatical postulate is not a result of an intelectual speculation and an ideological construct, but a reflection of past revolutionary movements.

What we mean by the autonomy and the Communist party? As a class proletariat can be autonomous only if it constitutes itself as a struggling class, which is aware of itself as a class and of its historical interest, that is the abolishion of the class society and therefore of itself, a fights exactly for this interest. However, we can not explain the autonomy only in terms of practical aspects of the struggle, such as class violence, attack against comodities, etc., as proletarians can carry them out without being fully aware of their meaning. The essence of autonomy is that they start to understand the meaning of their actions or that by themselves they develop class consciousness which makes it possible to move the struggle on a higher level. And as the emancipation of the working class is according to Communists really the task of the working class itself, autonomy can be born only in the process of class struggle, in confrontations with Capital, that will change the balance of forces between classes in favour of proletariat. In other words: class consciousness can come into existence only under a certain intensity of the proletarian struggle, only from a practical critique of capitalist social relations. Class consciousness is substantially linked to the proletarian struggle: it is a product of this struggle whose contents and form are at the same time expressions of an immediate level of class consciousness.

In the same way as it would be a mistake to ascribe the birth of autonomy to todays revolutionary minorities, it also can not be understood as a sort of miraculous moment, when the class gets somehow enlightened, it gains consciousness and becomes revolutionary. Even the birth and extension of autonomy are a practical and uneven process (and as we have seen on the example of movement in the Czech Lands, it is also reversible), in which the struggling class and proletariat’s historical interest are represented by those workers, who really fight and not those of them whose minds and acts are still stuck in the mud of reformism and counter-revolution. And in this process of fighting constitution and extension of autonomy, there is also the place of revolutionary minorities, which will sooner than the rest grasp, name and seek to realise individual steps of the historical programme of the communist revolution; minorities, which will give direction to the rest of the class movement (and not to manipulate with it in the sense of social democratic bourgeois politics).

These minorities will be born, will grow and multiply precisely due to the high intensity of the struggle, giving rise to a mass presence of class consciousness, which will, in turn, more and more obviously acquire the character of confrontation between revolution and counter-revolution. An effort to organise effectively the revolutionary side will lead to centralisation of those minorities as well as vanguard individuals and to the formation of the class’ revolutionary organisation – the Communist party. Therefore, the Communist party can not be defined according to formal features, but according to gathering the most advanced elements of the class and crystallizing and realising the Communist programme in their actions and conscious reflection of these actions.

In the light of everything said above, it is time to summarise and clearly name strengths and weaknesses of the proletarian movement in the Czech Lands at the end of the World War One and all the things following from them for living revolutionary “theory” – for the Communist programme. We are not interested in searching for the purest revolutionary movement, which we could triumphantly claim as is the case with many people, who shout: “Great! We have found another missing link in our family tree! It is the most leftist of all left factions – the guarantee of revolution!” We want to turn lessons from past struggles into a weapon against Capital! Unlike those, who have not got rid off the bourgeois conception of “scientific socialism” yet, we do not submit our class’ struggles to a however “radical” inquiry, but we discover and re-appropriate the invariable Communist programme in them. That is why it is important for us to see not only their strongest moments, but also mistakes done by our class brothers and sisters and hope, that thanks to them we do not have to repeat the same mistakes once again. We still fight not only the same enemy, that appears like the monstrous clown of the It! Movie and cheats us with colourful balloons, while crushing our bones and sucking our blood, but we also face the same weaknesses in the ranks of its potential gravediggers.

Let’s, thus, try to make a short balance sheet of the militant movement between 1917 and 1918:

- On the basis of necessity, the movement started to fight outside of trade unions and Social Democratic political organisations. As far as these organisations called on proletarians to passively suffer from declining material conditions of their lives until the war is finished or until national liberation realises the Republican mirage of social justice, the exploited’s radical minorities were forced to act on their own and emancipate from Left-wing channels neutralising our class’ subversive potential. Therefore even in the Czech Lands, re-constitution of class autonomy on the basis of intensive class struggle, self-activity of the class, rupture with embodiments of historical Social Democracy, with all the mediators and false friends of the working class, were confirmed as starting points for the birth of the revolutionary perspective. We have already discussed, how this struggle was going and what organisational forms it took on, including even the extent to which those organisations were able to attack the dictatorship of Capital in all its totality. It will, thus, suffice only to say, that though proletariat was taking its first steps towards its class autonomy, it was a contradictory process – primarily in the sense that the given level of the struggle did not bring about clearer conscious reflection of all the ruptures with bourgeois ideologies and the social project. Which is the reason, why the proletarian movement did not get from the struggle outside of unions and the Left to the struggle against them as its class enemies and let themselves to be recuperated by them anew.

- Even this proletarian experience of constituting and losing its class autonomy – on the basis of the beginning rupture with unionism and the repeated return into its pacifying and disorganising open arms – should be a warning for all militants of today, who are prone to believe taratiddles of all possible Syndicalists, Anarcho-Syndicalists, Trotskyists, Stalinists and other Social Democrats, that the working class will become revolutionary only organising itself in unions and leftist political parties. The history of our class’ struggles, however, reveals us the exact opposite: whatever unions (even painted in yellow, pink, red or red and black) and political parties (even if they call themselves federations and they are extra-parliamentary) stay in their social function on the terrain of Capital. That is why, one of the first steps workers take to constitute as the revolutionary class and as the Communist party, i.e. as the organised movement of the Communist revolution, is not just leaving the unionist-leftist framework of bourgeois organisations and reformism, but also a conscious and consistent struggle against them.

- And this is precisely what the class movement in 1917-1918 was unable to do. It was constituting its autonomy much more dynamicaly in practice than on the conscious level. Therefore, while in the strongest moments of the class struggle, many times workers were acting in an internationalist way, at the same time they were the bearers of the Left bourgeois programme of national liberation and national socialist republics. While internationalism was an expression of struggling workers’ strength as it was supporting extension of their struggle and constitution of the class fighting against Capital, national liberation proved to be a bane for the whole movement for it broke the movement apart and tied it to various bourgeois factions, prevented extension of struggle and diverted it on a blind track, disorganised and split proletariat as a class.

- Actual attacks against capitalist social relations were essential expressions of the movement too. On its peaks, it got from strikes for a lower rate of exploitation to practical critique of work in the form of intentional shirking and sabotaging the whole production process. Practical critique of commodities and monetary mediation between human need and its satisfaction was done through looting, field trespasses and banditism of deserters. Collective desertions and soldiers’ mutinies were a real refusal of a particular form of the dictatorship of Capital and bourgeoisie (embodied either by officers or the monarchy as a whole) and war among various factions of the ruling class. As we already said at the beginning, every struggle – perhaps only for higher wages or flour rations – directly attacked interests of the state waging war and, thus, in its essence it was “political“ and revolutionary: it was an expression of revolutionary defeatism, that by pursuing proletariat’s interests contributes to the defeat of “its own” state and ruling class. Inside thousands of acts and struggles, which were subverting so far sacred and unquestionable capitalist relations, and under the influence of proletarian struggles in Russia and the Ukraine, the birth of revolutionary perspective was begun. However, the given level of practical critique of social relations did not transform in systematic conscious critique. And the class consciousness crystallized only in a very vague form. It did not elaborate itself into a programme derived from the subversive practice of the movement and, therefore, at the last instance the movement accepted the programme of counter-revolution: national liberation, republicanism and chimera of social justice. In other words: it did not overcome its own original weaknesses and, thus, contributed to evoking conditions and forces, which made its recuperation possible.

- No movement is crystalline pure, without contradictions, and with workers equipped by the “correct” opinions and “correct” flags. In this respect, proletarian struggles of the last Austro-Hungarian years are no exception. Daily experienced capitalist exploitation and oppression were often erroneously understood by fighting proletarians as national oppression. The fact, that the part of bourgeoisie, which was responsible for moulding general conditions, in which their exploitation took place (the state and government), was organised on a national basis (predominantly German-Hungarian), obscured the global nature of capital and the fact, that their outright exploiters (bourgeoisie directly buying their labour force: factory owners and their directors, land owners) were coming from all nations. For instance, that is why, striking workers in a factory talk about the “Austrian oppression”, even if they are actually rebelling against the oppression imposed on them by Capital. This contradiction between half-hearted conscious expression of their interests and their radical practice appears again and again in every proletarian revolt. In many places, proletarians were entering conflicts with Capital, while armed only with feeble and basicaly counter-revolutionary phrases, but at the same time they were able to practically subvert capitalist relations around themselves. Nationalist rhetoric about a construction of the glorious empire and immortal emperor on one hand and the prison of nations on the other one, found a fertile ground in weaknesses of proletarian consciousness. Nevertheless, they could not prevent, for example, angry soldiers – proletarians in uniforms – from refusing to suppress strikes and hunger riots from time to time, even if their commanders were sending them for this purpose across half of the monarchy, for instance from Hungary to Sudetenland. However, on the other hand, bourgeois flags have always marked the limits of every struggle, if proletarians were not able to throw them away on the basis of their own practical experience.

nhIt is not possible to conclude our modest contribution to a critical reflection of the first act in a revolutionary drama, played by proletariat in the Czech Lands and Slovakia too in the last years of the world war and two following years, without putting this drama into the context of a much wider drama: the revolutionary wave, which then shook the world and forced competing bourgeois camps to stop the war before Capital really needed to do so. Only in this worldwide framework, the local events can reveal their meaning for our class, which is as global as Capital. The movement analysed by us was an indivisible part of this framework and from a global viewpoint it was actually one of episodes in the world revolutionary drama. And surely it was not one of the most important episodes, one of the peaks of the class movement.

In 1917-1918, real peaks and epicentres of the proletarian revolution could be found primarily in Russia, the Ukraine and Germany. It is not that revolutionary movements in these countries did not suffer from internal contradictions. But in the process of combat constitution of class autonomy, the most militant workers’ minorities (industrial and agricultural as well) made a qualitative leap in their class consciousness, conditioned by practice and influencing practice, which led them to attempts at imposing the social dictatorship of proletariat, i.e. the dictatorship of human needs over Capital and Economy. There were also the first expressions of an organic growth of the Communist party, however contradictory they were and whatever they called themselves: Marxists, Anarchists, Maximalists, Red Guardists, Black Guardists, Revolutionary Insurgents, Communists…

Why this was not the case also in the Czech Lands? In all modesty, as far as we can at least sketch an answer to this question, it seems to us, that the reason does not lie in the rate of exploitation and changes in its organisation, in particular magnitude of suffering and horrors, which proletarians in this or that country were exposed to. All of this undeniably stands behind the boom of class struggle and the birth of workers’ autonomy, but its development or set backs had also something to do with weaknesses of the movement itself and bourgeois ideologies, whose pillars were reproduced by workers themselves and whose influence they were exposed to at the same time. Precisely, the weight of ideologies combined with material conditions and class struggle formed the proletarians’ perspective.

More precisely, in Russia, Germany and the Ukraine the old materialisations of Social Democracy (trade unions, Mensheviks, Esers and the SPD) clearly and actively supported the war, which called in as clear response on the proletarian side. The most militant minorities of our class stood up against these bourgeois parties and, based on strength and weaknesses of workers minorities, the extreme-Left opposition grew already during the war. Even during the later rise of class struggle, beginning by the end of 1916, there is a clear confrontation with the combative part of the class and the openly pro-war Social Democracy. However, politics of the CSSDWP was not so beautifully transparent. Neither it actively supported the war nor opposed it actively; simply it aided the war effort calmly and mainly through its passivity. (55) So, even the most radical proletarian minorities shared many illusions about the CSSDWP still at the end of the war. And for those, who did not believe “Marxists” of the Second International, there were National Socialists and their “Anarchist” lackeys waiting and posed like a consistent anti-war and pro-worker alternative.

These blunted points of confrontation between Social Democracy and the class movement were compounded by the main weakness on the side of proletariat itself: belief in national liberation. While neither in Russia nor Germany it was on the order of the day and in the Ukraine it was limping belatedly behind the proletarian revolution, in the Czech Lands, but also in Slovakia (to a much lesser extent) and Poland, it was, together with Republicanism, evoking a confused idea, that social revolution is identical with a national liberationist changeover and a reform of the bourgeois state. If the proletariat in Russia, the Ukraine and Germany was clashing with the state in certain moments, in the Czech Lands it allowed itself to be used for overthrowing the monarchy and proclaiming the Czecho-Slovakian national state. Its frontal conflict with the ruling class and its state was postponed by two years, which allowed the international bourgeoisie to create the Central European sanitary cordon separating revolutionary Germany from the Ukraine and Russia. It also gained time and created conditions for the victory of Social Democratic counter-revolution in these three countries and all this contributed to the fall of council republics in Hungary, Slovakia and the Carpathian Ukraine, or better said, to the fall of proletarian movements, which gave birth to these republics on one hand and were framed, tamed and liquidated by them on the other.

In spite of the failure of the movement in the Czech Lands in 1917-1918 to overcome its original limits and to go as far as in the epicentres of revolution, it is necessary to say, that its weaknesses are essentially identical with weaknesses of the movements in Russia, Germany, in the Ukraine, but also elsewhere, even though they expressed themselves in an another way and on another levels over there. In their majority these movements reproduced the concept of nation, which then materialised itself in the form of nationally structured socialist council republics. The fact that the international movement as a whole failed to develop a total revolutionary attack against Capital and State – the real proletarian dictatorship and communisation of social relations – led to Social Democratic counter-revolution of Lenins, Trotskys, Noskes, Eberts… Yes, in certain respects some revolutionary minorities went further than the rest of the movement, but while realising their social project even they did not get any further than to a sort of self-managed capitalism based on labour communes or workers collectives. They did not get from the question, “Who shall be the boss in Communism?”, to the question, “What shall be bossed and managed?” Nevertheless, only thanks to the gigantic experience of the world revolutionary movement, today we are able to say much more precisely, what Communism is not and what is or is not subversion of Capital about.

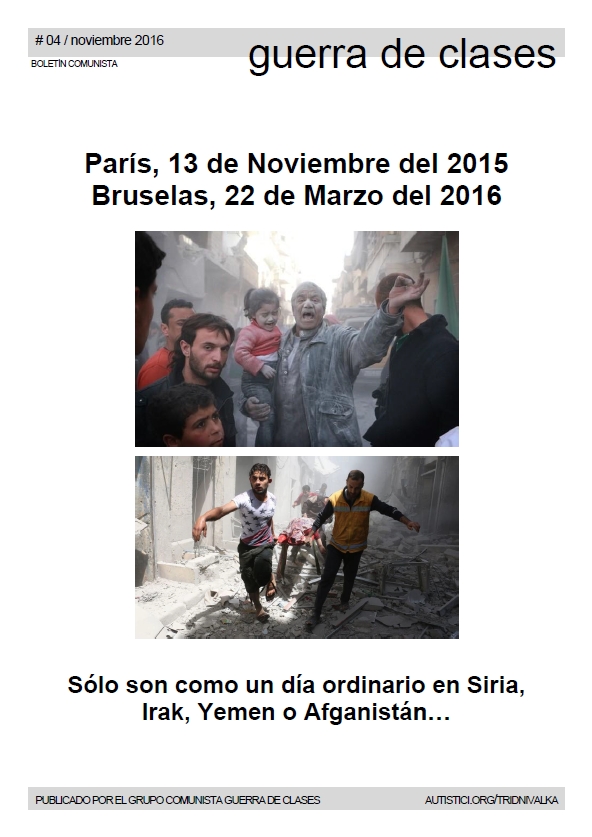

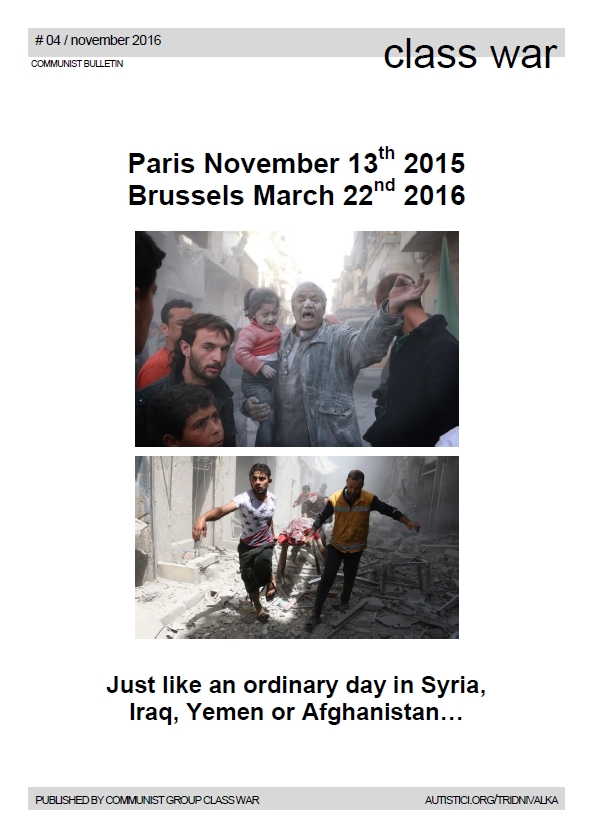

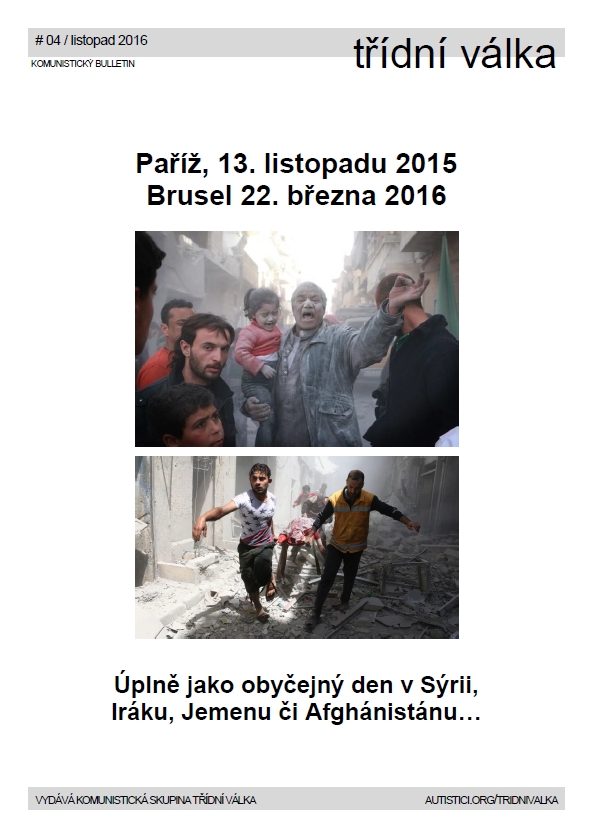

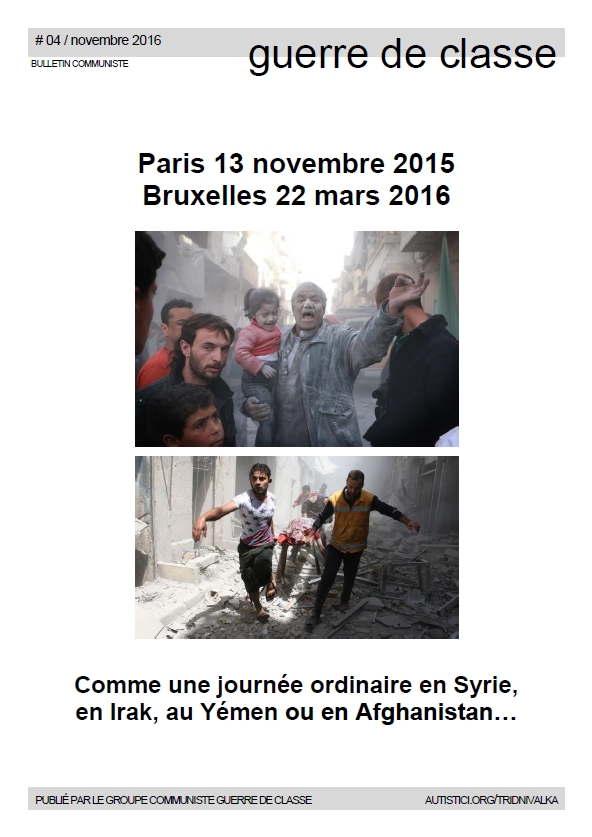

Just as at the end of the World War One, even today proletarian movements are full of internal contradictions. It is all the more like this, because we are not on the eve of the worldwide revolution, but on the contrary in a period of defeat and general atomization of our class. When nowadays proletarian anger erupts in an open conflict with Capital, workers on the other side of the world or even in a neighbouring country tap on their foreheads, why the Islamists, peasants, immigrants or separatists are fooling around. Even bourgeoisie uses these contradictions, when it needs to strengthen its domination over proletariat. Deserters from the Serbian army and demonstrating workers in Sarayevo suddenly change by a magic trick into agents paid by the USA, who deserve to be shelled from cannons, or into fighters for freedom and independent Bosnia – it depends which TV you are watching. Armed guerillas of agricultural proletarians from soya plantations in Somalia are labeled as Islamists, striving for Sharia codex and blood of non-believers, who must be suppressed by the Ethiopian military. Young proletarians fighting for life with the police on poor Parisian suburbs are just a bunch of immigrant gangsters, who do not revere the French state’s hospitability.

On the basis of studying the class movement in 1914-1918, we are not able to scientificaly reveal, which constellation of objective and subjective conditions reliably gets proletariat to move; which conditions lead it towards ever more intensive struggle, in which it overcomes all physical and ideological separations through which they are structured and divided by Capital according to its needs, towards the struggle from which class autonomy and revolution will be born. Communism is not a science, it is a living movement coming from present capitalist relations and subverting these relations. It does not move according to firmly given laws, which will inevitably lead our class to revolution and realisation of the worldwide Communist community project. Communist revolution and society are not a historical necessity, which will come willy-nilly and which the proletariat will blindly realise. Communist revolution and society are just the only possible overcoming of capitalist inhumanity through self-abolishion of the proletariat and thus also Capital, State and all the class society. This self-abolishion, however, can not be an unconscious act. Without choosing between Communism and barbarity there will be no qualitative leap from class autonomy to the revolutionary subject of history. And this is true today as it was in 1917…