“An injury to all”: the class struggle is back in Italy

As Renzi’s center-left government intensifies the project of neoliberal restructuring, a wave of self-organized class struggle takes off across Italy.

As Renzi’s center-left government intensifies the project of neoliberal restructuring, a wave of self-organized class struggle takes off across Italy.Back in 2006, Warren Buffet, the notorious billionaire speculator, confessed during an interview that: “There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.” Since then, that class warfare has been ever tougher in Italy. Since 2000, real wages have been decreasing, registering an even sharper downturn since the beginning of the crisis in 2007-’08. In real terms, wages nowadays are as high as in 1990.

At the same time, unemployment has skyrocketed. The number of unemployed people was registered at 3.23 million in September 2014. Italy’s jobless rate increased to 12.6 percent in the same month, while its youth unemployment rate (aged 15-24) was 42.9 percent. In September 1983, the two rates were respectively 7.5 and 25.9 percent, respectively. The Gini coefficient, the most common measure of economic inequality, has gone back to the same levels of the 1970s. In 2012 it averaged out at 34.9 per cent, a level as high as in 1979.

But probably, since the beginning of the last economic crisis (2007-08), the most evident indicator of the ongoing class war in Italy has been the increasing disposal income of the bourgeoisie and the steadily decreasing income of the working class, which shows to what extent the crisis has been an opportunity for the rich to privatize profits and socialize losses.

A Clear Political Project

The ongoing class war in Italy is not a byproduct of “natural” global economic developments. On the contrary, it is a clear political project carried out by the center-right and center-left governments that have ruled Italy for the last thirty years. The aim of this project has been to consistently deteriorate the improvements in the living and working conditions that the working-class movement obtained during the revolutionary wave of the 1970s, with the goal recreating the bosses’ mirage of cheap and disciplined labor that could attract international capital to Italy.

Particularly, since the beginning of the last economic crisis, the neoliberal project set up by the Italian bourgeoisie along with its European partners in the 2011 memorandum has become the political agenda of the last three governments, led respectively by Monti, Letta and Renzi (none of whom, incidentally, were elected by the Italian people).

The first of the three sections which composed the memorandum has been the enforcement of austerity measures meant to drastically reduce the state’s expenses for local administrations, infrastructure, welfare, schools and healthcare. These measures triggered the fierce resistance of the student movement back in 2008-’11 against the Gelmini school reform, and the outburst of the anti-austerity protests more recently focused on the housing problem.

The second section has consisted in a wave of privatization, which has involved mainly the transport, telecommunication, and post services against which, last winter, tough protests were organized by workers and users — protests that are likely to rise up again very soon.

The third and final section of the memorandum deals with the labor market and aims to entirely deregulate it. At the moment the current government is trying to enforce this labor policy through a package of laws called the Jobs Act. This agenda constitutes the political manifesto of the Italian bourgeoisie — to the extent that the President of the Italian Industrialists Association (Confindustria), Giorgio Squinzi, recently referred to Renzi’s labor policy as “a dream come true.”

A Wave of Mobilization

The effort to pass the Jobs Act in Parliament has triggered a wave of mobilization in the working class all over the country. Even the until-recently innocuous trade union CGIL was forced to step in and call for a huge demonstration in Rome at the end of October and a general strike on December 5. In the meantime, workers are striking and protesting as they have not done for many years, against the Jobs Act and in defense of their jobs.

This violent attack against workers is rightly understood as the next step of a political project aimed to impose precarity as the standard living condition for all the lower classes — “all those who produce and reproduce urban life.” That is why it was possible to unify the struggles which cross society against the school reform and the austerity measures, particularly the right to housing, on November 14.

On that date, along with the general strike called by most of the main rank-and-file unions and by the biggest metalworker union, FIOM, thousands and thousands of people took the streets with the goal of blocking the circulation of goods and people in the main Italian cities. The day of mobilization started early in the morning with blockades at the entrance of several warehouses and working places.

In Pisa, the workers of AVR blocked the entrance to the offices of the subcontracted cleaning company which is seeking to worsen the working conditions and reduce the wages. Later on, the same workers along with local activists joined the workers of GB at the local airport where they had to clash with cops to win the right to protest against the working conditions imposed by a company which is gaining millions of euros out of the management of the airport.

As for the students, lessons were interrupted in many universities, including the Federico II University in Naples. In Rome, the housing action movement occupied the offices of the local water provider, ACEA, to protest against the interruption of water service for users who are insolvent, while other activists along with many families in need of housing squatted a huge empty building, the former headquarters of a big Italian banking group, BNL.

At the same time, in Naples the registry offices were occupied against the Lupi plan which refuses to grant legal residence to those living in squatted houses. The Florentine housing action movement occupied a central junction paralyzing all traffic in the north of the city, the area with the highest percentage of squatted spaces.

In the middle of the morning, rallies and marches took place all over the country. Turin, Milan, Bergamo, Brescia, Genoa, Padua, Verona, Treviso, Venice, Bologna, Rimini, Florence, Pisa, Massa, Rome, Naples, Palermo, Olbia are only some of the many cities which were crossed by thousands of students, workers and activists throughout the country. All the demonstrations marched through the main roads to block the circulation of goods and workers over urban space as much as possible.

Clashes with riot police occurred in many cities, the harshest in Milan, Pisa and Padua. In several cases, such as Naples and Florence, the demonstrations ended or passed by the offices of the Industrialist Association, which was targeted by the demonstrators. This association has been rightly understood by the class movement as the real enemy which, along with Renzi’s government, is responsible for the current labor policy and precarity in every aspect of the life of the lower classes.

Resistance, Unity, Organization

Three words capture the political agenda that the working class and the social movements are currently trying to put into practice. The first one is resistance. Resistance against the political project that the Italian and European ruling class is enforcing over our lives. The laboring classes need to be faithful in their means of opposition, and not to think that the battle is already lost.

The second one is unity. Unity among those “whose only possession of significant material value is their labor-power.” This is the strong message which comes up from the November 14 day of mobilization, as the decision of the main rank-and-file union of the logistic sector, SiCobas, to march along with the metalworkers in a huge demonstration in Milan clearly shows.

The third is organization. The current enthusiasm cannot be enough to win the battle against Renzi’s government and its policy of enforced precarity. There is a need to organize the action of the subaltern classes in the long run and take advantage of different forms of direct action.

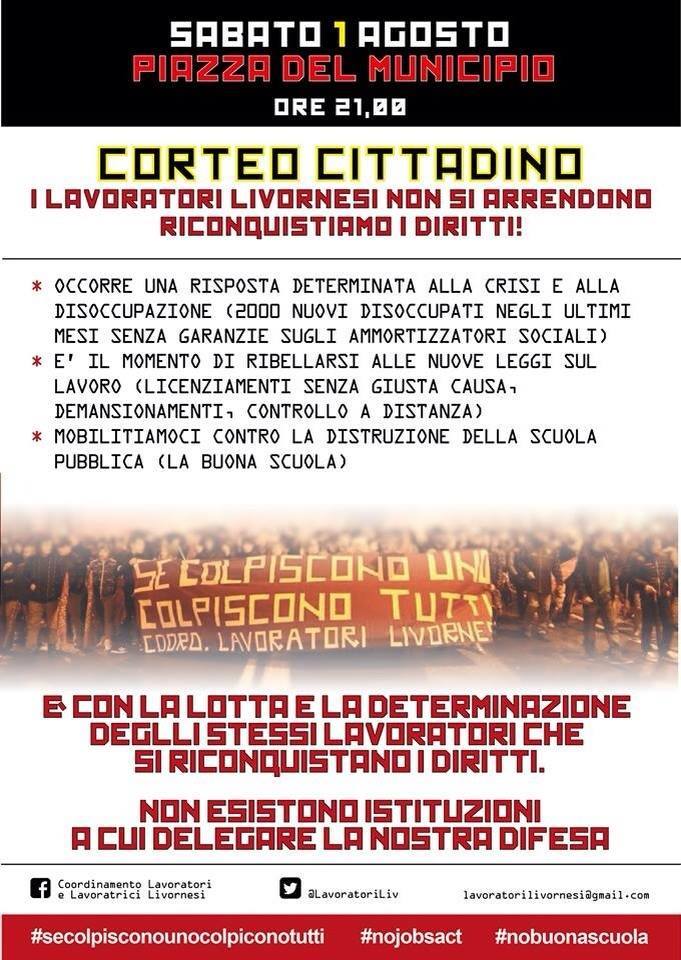

A concrete example of this political counter-project was put in place in Livorno where the recently formed Coordination of Workers of Livorno has been able to mobilize the whole city in support of their struggle against the loss of more than 2.000 jobs in the wider urban area. Last Saturday, notwithstanding the heavy rain, more than 3.000 workers, students, football supporters, housing-action activists and common people took to the street in an outstanding march which crossed the city, while most of the small retailers were closed in solidarity with the workers.

The Coordination in Livorno is a self-organized initiative which brings together hundreds of workers, mostly rank-and-file union representatives, from all over the urban area of Livorno. The concept behind this project is as simple as it is powerful: workers have common interests and their struggles are stronger when they are united regardless of who their employer is and which economic sector they are employed in. Despite the fact that the Coordination is only a few months old, it has already been able to put the labor issue at the forefront of the political agenda of the city.

The Livorno experience has proven that grassroots movements of workers, students and common people can be effective and can become the voice of the majority of the population. However, obstacles and enemies are opposing this possible development. A growing racist anger, which tends to divide migrants from the rest of the class, is growing in the suburbs of the Italian metropolises promoted by fascist groups, such as Casa Pound, and xenophobic parties, such us the Lega Nord, all over Italy, as the recent cases of Bologna and Rome demonstrate.

Nonetheless, the days of mobilization of November 14 and 15 open a path to be followed in the “everyday gray labor” in the working places and in the neighborhoods, and at a national level in the coming days of countrywide struggle — such as the general strike called by the CGIL on December 12. The class struggle is back in Italy and will shake our country for some time to come.

Alfredo Mazzamauro is a PhD researcher in History at the European University Institute in Florence

Original source: Roarmag

see also: